From the Winter 2024 issue of Living Bird magazine. Subscribe now.

Kristen Heath-Acre lives in Columbia, Missouri, which officially has a sister-city relationship with Hakusan City, Japan.

But Heath-Acre, the state ornithologist for the Missouri Department of Conservation, says she feels more of a sister-city connection to the town of Santa Marta and the mountain forests near the coast of northern Colombia. Because by looking at a new set of maps produced using eBird data—called eBird Shared Stewardship Maps—Heath-Acre can see that Missouri has a special connection with the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, as the winter home of Cerulean Warblers and other migratory songbirds that breed in the Show-Me State.

According to Heath-Acre, recognizing those special migratory-bird connections between places in the north and south is a key to effective conservation for these species that fly up and down the hemisphere.

“Birds on the whole are disappearing. Their populations are declining,” she says. “And so if we are trying to support birds on the whole here in the U.S., we have to look at their whole life cycle, what’s happening throughout the year.”

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology produced these data-driven maps in collaboration with Partners in Flight, a consortium of bird-conservation scientists in the Western Hemisphere. Increasingly, scientists are emphasizing the importance of full life-cycle conservation—preserving and protecting the habitat that a migratory bird needs for both its breeding and nonbreeding periods.

Visualizing Where “Our” Birds Go When They Leave

“We often think of birds as belonging to our states, or belonging to where they are when they’re breeding,” says Sarah Kendrick, a migratory bird biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “But really, we’re only hosting these birds for a few months of the year. They’re pretty much tropical birds.”

For example, eBird data show that a Cerulean Warbler in Missouri’s Ozarks has a breeding window of about 49 days before preparing for migration. But almost half of that bird’s year—an estimated 149 days—is spent in Colombia during the nonbreeding period.

“We share those migratory bird populations with our conservation partners across the hemisphere,” says Kendrick. “And we know that they’re facing major threats throughout that full year. These eBird stewardship maps help to paint that picture in a really cool visual way, of where our shared birds are traveling beyond our borders.”

The maps are powered by a dataset that consists of 44 million eBird checklists submitted by birders from 14 million locations throughout the Western Hemisphere from 2007 to 2021.

“It’s a lot of data, and basically we can see each species observation in each checklist as a data point,” says Archie Jiang, the Cornell Lab computer programmer who generated the Shared Stewardship Maps. Jiang graduated from Cornell University in May 2023 as a computer science major, and he was an officer in the Cornell Birding Club as an undergrad. “We have this space and time data of where people are observing birds, and this is the raw data that we’re working with.”

Jiang fed modeled eBird data into a sophisticated program (developed by Cornell Lab data scientist Matt Strimas- Mackey) that identified places where migratory birds are concentrated in the nonbreeding season. He then weighted those results by the proportion of bird breeding populations that occur within a targeted state or region, essentially highlighting parts of the map where those birds go on migration. For example, he found that Black-throated Blue Warblers that breed in New York State show a very strong migratory connection to overwintering grounds in Jamaica.

Shared Stewardship Maps

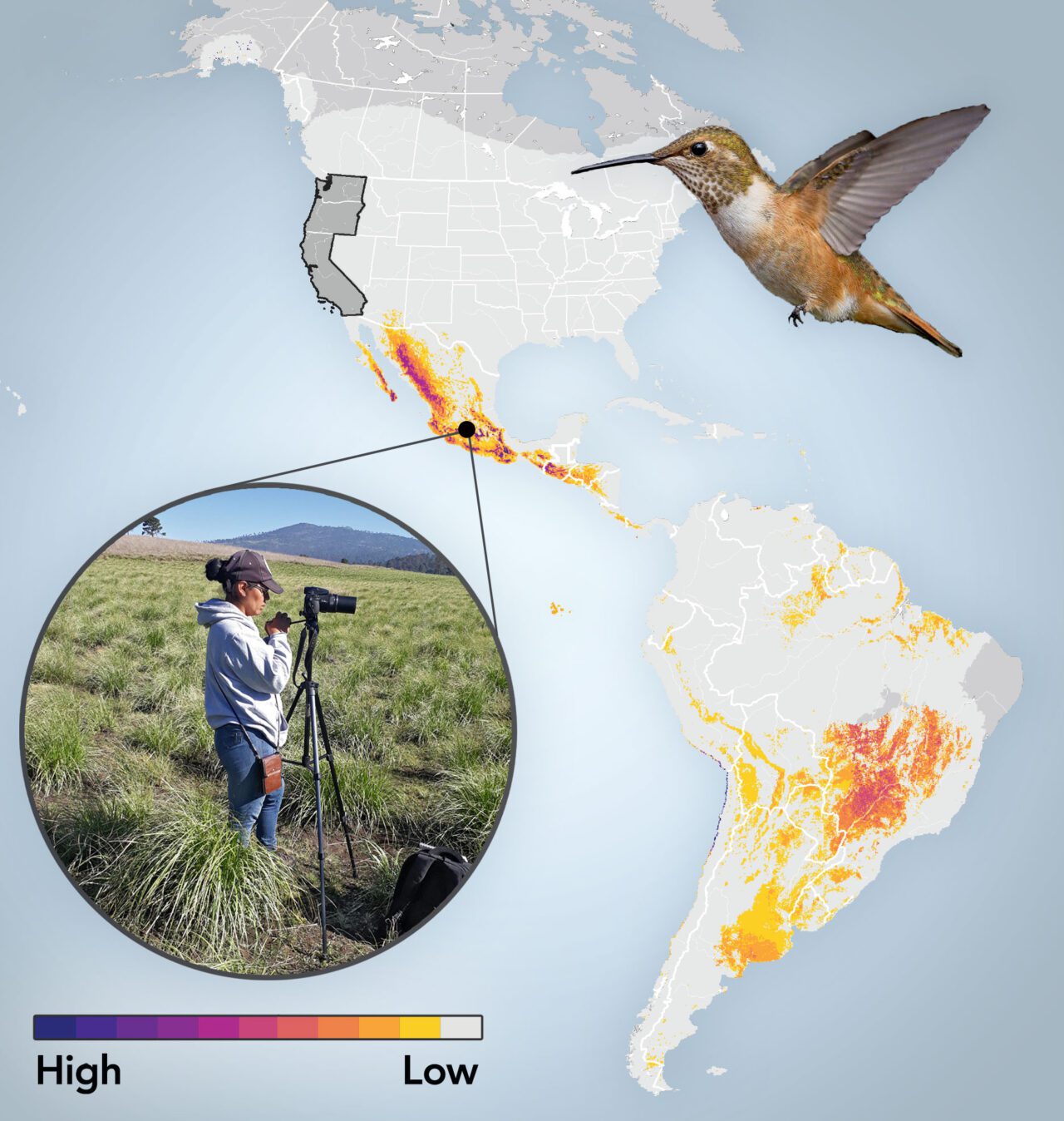

West coast: Linkages for 48 Breeding Species

Rufous Hummingbirds connect the West Coast with Mexico City. In an Indigenous community just south of Mexico City, the Brigada de Monitoreo Biológico Milpa Alta of San Pablo Oztotepec is working to restore subalpine grasslands. This area acts as a year-round refuge for the endemic, endangered Sierra Madre Sparrow, as well as an important overwintering area for Rufous Hummingbirds for 100 days of their nonbreeding season. Urban sprawl threatens the area, but local Indigenous leaders are driving efforts to study, conserve, and sustain the biocultural heritage of their people and their land.

Midwest: Linkages for 84 Breeding Species

Spotted Sandpipers Connect the Midwest with the Peruvian Coast. All along the Pacific Coast of South America, the nonprofit science group Center for Ornithology and Biodiversity (aka CORBIDI by its Spanish acronym) is working to monitor and protect areas for shorebirds. CORBIDI scientists organize shorebird surveys along the Peruvian coast every four years and load their data into eBird. Their survey data was recently used to nominate and gain government protections for an area of mangroves in northern Peru that had been identified as an important area for Spotted Sandpipers and other shorebirds.

Northeast: Linkages for 74 Breeding Species

Rose-breasted Grosbeaks Connect the Northeast With the Ecuadorean Andes. Within the Choco Andino Biosphere region, the Mashpi Chocolate farm is regenerating forest that provides food and acts as nonbreeding-season habitat for migratory songbirds such as Rose-breasted Grosbeaks. More than 80% of the farm’s 140 acres have been restored to forest, with more than 200 bird species counted in the latest survey. The farm’s sustainable cacao production carries a Garantía Agroecológica certification—meaning no chemical pesticides or fertilizers are used in producing Mashpi’s fine artisanal chocolate and cocoa delicacies.

Methods Summary: eBird Shared Stewardship Maps with uniqueness nonbreeding connections are generated by calculating the sum of nonbreeding bird abundance in each 3×3 km grid cell for all migratory bird species that breed within a focal region, then weighting by the percent of each species’ breeding population in the focal region. The results are then divided by the total sum of stewardship connections for all regions in the U.S. to emphasize the uniqueness of shared stewardship connections for a particular focal region.

“Birds are one of the things that can link us across large spatial scales,” says Cornell Lab quantitative applied ecologist Andrew Stillman. “These connections have existed for thousands and thousands of years, but they’re really hard to understand. They’re invisible.”

Stillman says that in recent decades, the advent of radio- and GPS-tag tracking technologies allowed scientists to get a glimpse of these migratory connections between places; put a tag on a bird, track it as it flies south, and see where it spends the winter.

But while tracking tags are good for studying individual birds, they can’t yield data that’s useful at the scale of entire populations.

“The ideal information [for conservation scientists] would be if we put a tag on every single, stinking bird in the entire U.S., but we can’t do that,” Stillman says. “These eBird Shared Stewardship Maps provide us with baseline information at the species level.”

Deb Hahn, the international relations director at the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, is putting those eBird maps to good use. Hahn directs the Southern Wings initiative, a partnership of state agencies that connects states with conservation groups in Latin America. Hahn says the eBird Shared Stewardship Maps are extremely valuable in her efforts to show the biological connection between areas in the U.S. and areas south of the border, as she facilitates full life-cycle conservation projects for migratory birds.

“The stewardship maps can help a state agency get a sense of … what areas might be a great place for them to invest in to have more impact on the greatest number of species,” Hahn says.

Through Southern Wings, 41 state agencies have donated nearly $3.9 million to projects in 11 countries in Mexico, Central and South America, and the Caribbean. Hahn thinks the eBird maps will stimulate more such cross-border conservation.

“Having the maps helps us make a stronger case for the need to put conservation dollars in specific areas,” she says.

Importantly, say Cornell Lab scientists, these maps should set the stage for true collaboration between conservation biologists in the U.S. and Latin America.

Setting the Stage for Collaboration

“Ideally, we’re looking at these maps together. That’s really the whole idea behind shared stewardship,” says Viviana Ruiz Gutierrez, a native of Costa Rica who’s the director of conservation science at the Cornell Lab. “It’s not to try to impose a point of view or priority, but it’s more to know where to look for partners and contribute to conservation efforts that are already on the ground in Latin America.”

For example, when the Missouri Department of Conservation wanted to enhance the effectiveness of their conservation funding to turn around declining populations of long-distance migratory birds such as Wood Thrush (a state-designated Species of Greatest Conservation Need), they looked to Latin America—via Southern Wings—to partner up with the Colombian conservation group SELVA.

“SELVA’s recent research on migratory birds has seen huge benefit from cross-border collaboration with U.S. and Canadian government agencies,” says Camila Gómez, a director at SELVA. “These funds go a really long way in Latin America. They have served to employ and build capacity of local researchers, implement research and conservation activities on the ground, and highlight the importance of broad international collaborations to guarantee migratory bird welfare throughout their annual cycle.”

Heath-Acre says she’s proud that Missouri was a leader in the paradigm shift toward full life-cycle conservation.

“These birds don’t realize these borders exist,” she says. “I think Missouri has done a really good job of following the birds where they go, providing funding and support for research where these birds are going.”

According to Sarah Kendrick of the USFWS, the eBird Shared Stewardship Maps could be a catalyst for ramping up full life-cycle conservation efforts. And that’s desperately needed, as U.S. federal and state agencies work to turn around a massive 26% loss among all Neotropical migratory bird populations since 1970, according to research published in Science in 2019.

Says Kendrick, “If we’re not addressing the threats that these birds face when they’re beyond our borders, we’re not doing all we can.”