Manonichthys paranox, the Midnight Dottyback. Photo credit: Lemon TYK.

Mimicry is an ancient art practiced and mastered across the board in the animal kingdom. The paradigm of mimesis is a multifaceted prism, each with unique modifications to the standard model. In a precarious world where “eat or be eaten” is the central dogma, organisms must evolve certain tricks to enable survival and proliferation. No one said that these have to be boring though, and as evolution would show, nature is a magician with a bottomless pit for its hat of tricks.

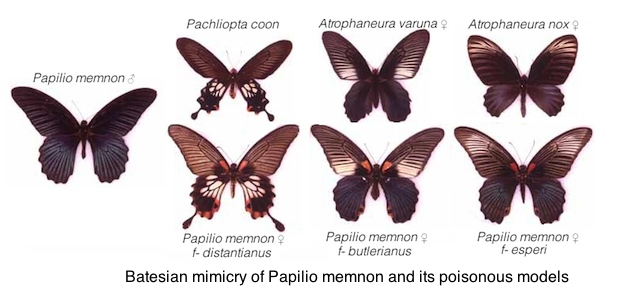

In the discussion of mimicry, no other group of organisms embody this to greater lengths than insects. Some of the more iconic, classic examples of mimesis center around the field of entomology, where batesian and müllerian mimicry are notoriously well represented. In the former, a harmless, vulnerable species seeks protection by copying a known, distasteful or toxic model. By masquerading under false colors, the palatable insect is rendered invisible to predators, sans the subtle nuances that humans have come to appreciate. This is well studied in Papilio memnon – a large tropical swallowtail butterfly with polymorphic females that mimic various toxic species. In müllerian mimicry, two or more similarly toxic animals mimic each other to seek protection as a group, increasing the chances of survival.

While these models are widely featured in terrestrial organisms, the same can be applied in the realm of piscines as well. The venomous Meiacanthus fang blennies are well known for their painful bites, and so serve as models to a wide variety of faux representatives. Cheilidopterus and juvenile Scolopsis are well known batesian mimics who swim under the pretense of these bennies. A more common model adopted in the reef, however, are protective resemblance and aggressive mimicry. In the former, organisms cover and conceal themselves by adopting the form and colors of their environment. Some well known examples include sponge-mimicking frogfishes (Antennarius) and the highly perplexing ghost pipefishes (Stolenostomus).

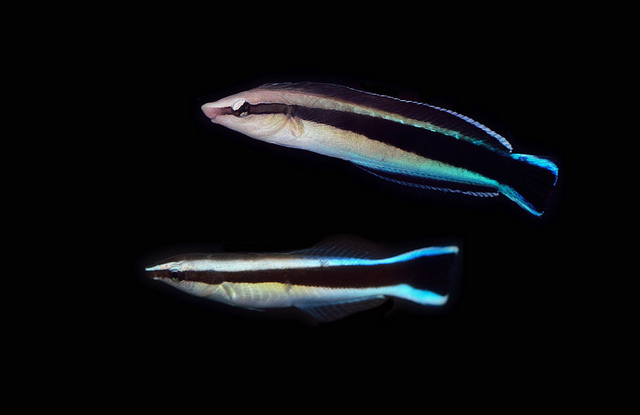

Even more diabolical still, is the adoption of aggressive mimicry. In this scenario, an animal adopts the color of a friendly species, exploiting its guise to sneak up on prey. The genus Plagiotremus and Aspidontus, both opportunistic carnivores, have evolved in great tandem with their models. The sinister and malevolent Aspidontus for example, mimics the cleaner wrasse Labroides dimidiatus, and with its masquerade, brazenly swims up to unsuspecting fish where it takes a chunk out of its flesh.

This model of mimicry is also adopted by a lesser known genus of dottybacks, one that lives in seclusion amongst the catacombs of shallow water reefs. Manonichthys – “Manon“, a type of sponge, and “ichthys“, for fish – is a genus of largely mimetic dottybacks so named for their preference of sponge dwelling. They are somewhat bulky, aggressive, and mostly predatory. A couple of species stand out for their impressive mimicry, in which they exploit to creep up on unsuspecting prey.

Manonichthys paranox is a medium sized dottyback distributed primarily in the Bismarck Archipelago, including Papua New Guinea and the Northern reaches of Australia to the Solomon Islands . As its name suggests, the fish is completely jet black sans a brick red iris and eye ring. The species is a faithful mimic of the dwarf angelfish species Centropyge nox, down to habitat preference and its unusual swimming style. Its enlarged, lobular pectoral fins are flicked in the same manner as its Pomacanthid model, and coupled with the typical cautious movements, makes for a very convincing act.

By adopting this visage, the dottyback is able to swim without suspicion along side the smaller fish in which it preys on. There is also some benefit to this disguise that transcends that of a predatory nature. Dwarf angelfish are notoriously cunning and evasive, capable of frustrating even the most skilled hunters on the reef. As such, most predators have learned to avoid the chase, as chances are, their efforts would end in fruitless futility. By mimicking a dwarf angelfish, Manonichthys paranox therefore gains an added protection from quasi-müllerian mimicry (although neither are toxic or unpalatable). The surgeonfish species Acanthurus pyoferus is also a well known Centropyge mimic in its juvenile stage, copying the Centropyge species C. eibli, C. flavissima, C. vroliki and even their hybrids in overlapping ranges. The protective benefits of masquerading as a dwarf angelfish is quite likely more effective than first thought.

Taking the mimicry game to another level is Manonichthys jamali from West Papua. Like M. paranox, this species adopts aggressive mimicry to sneak up on its prey. In this case, the damselfish species Chromis retrofasciata serves as its model.

M. paranox is quite the quintessential “book fish”, with very little known about its behaviour. This specimen photographed and videoed in situ at Cairns Marine likely represents one of few live photos and videos available of this species. The specimen was collected by Tyson Bennett at the Northern Great Barrier reef at a depth of about six meters.

This article was first published on November 25, 2015.